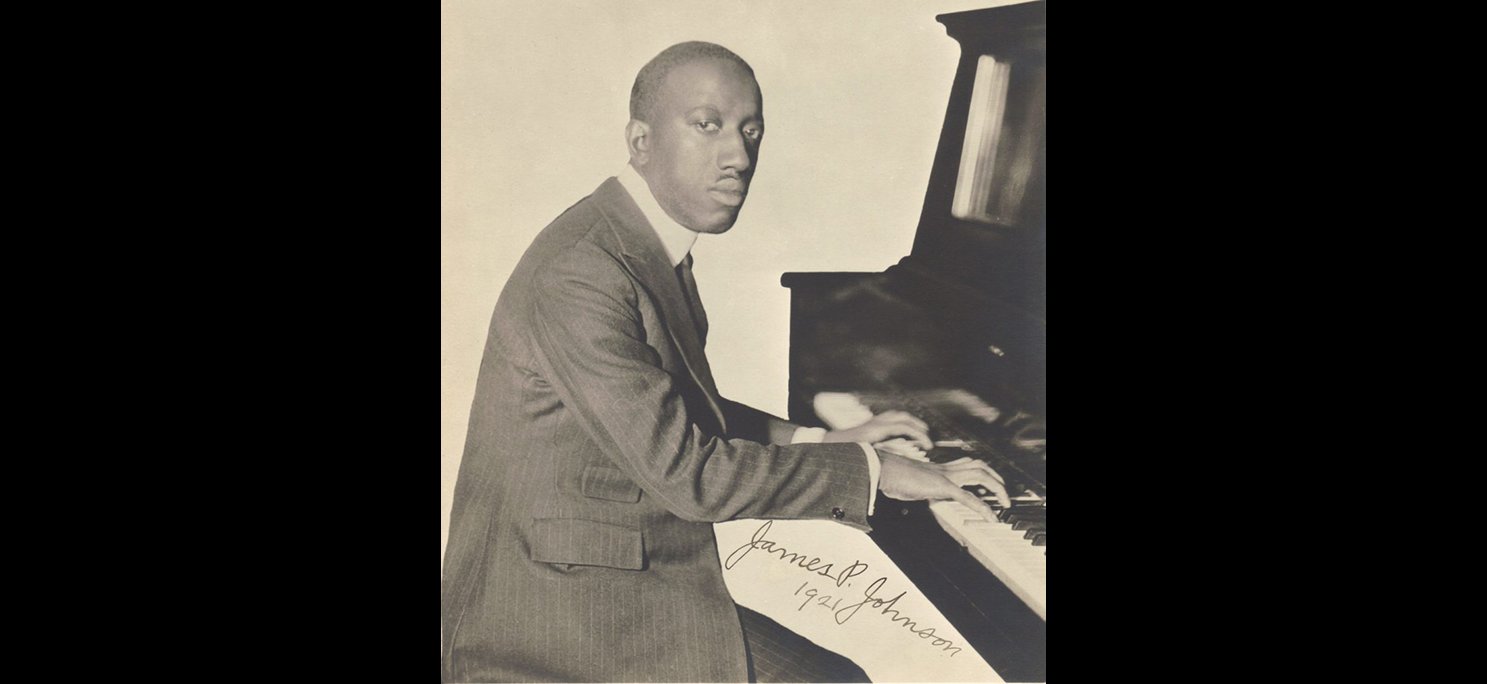

George Bellows, Both Members of this Club, 1909.

Photo: National Gallery of Art.

George Bellows

and the Battles of San Juan Hill

July 29, 2025

by Robert W. Snyder

The streets of old San Juan Hill are gone, vanished under urban renewal and construction. It takes an informed imagination to stand at the corner of West 65th Street and Broadway, and conjure the same spot in 1909—when artists lived and worked there at the Lincoln Arcade, fight fans cheered boxers at Sharkey’s Athletic Club across the street, and Black and white gangs warred nearby.1 We can enter that world if we study the work of the artist George Bellows, an Ohio transplant who moved to New York City in 1904 and lived and worked for a time at the Lincoln Arcade.

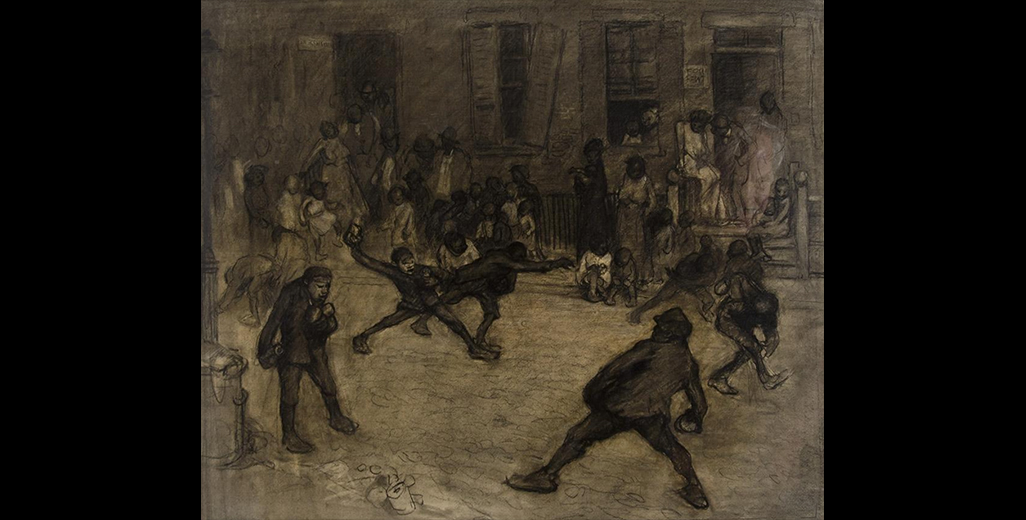

Bellows first made a name for himself as one of a circle of painters called the Ashcan Artists, who clustered around their mentor Robert Henri, a painter and teacher who exhorted artists to combine the journalist’s first-hand observations of city life with techniques of classical painting to produce original works that were firmly grounded in their time and place. Bellows put Henri’s teaching to use in two works that reflected life in the streets of San Juan Hill and Lincoln Square, the oil painting Both Members of this Club (1909) and the crayon, ink and charcoal drawing, Tin Can Battle, San Juan Hill, New York (1907).2

At the dawn of the twentieth century, San Juan Hill was home to New York City’s largest African American community. Black settlement there was the product of a long process of migration in the second half of the nineteenth century as African Americans moved from Greenwich Village north along the West Side to the Tenderloin and eventually Harlem. Every step of the way involved turf wars, turf claims, and institution building.3

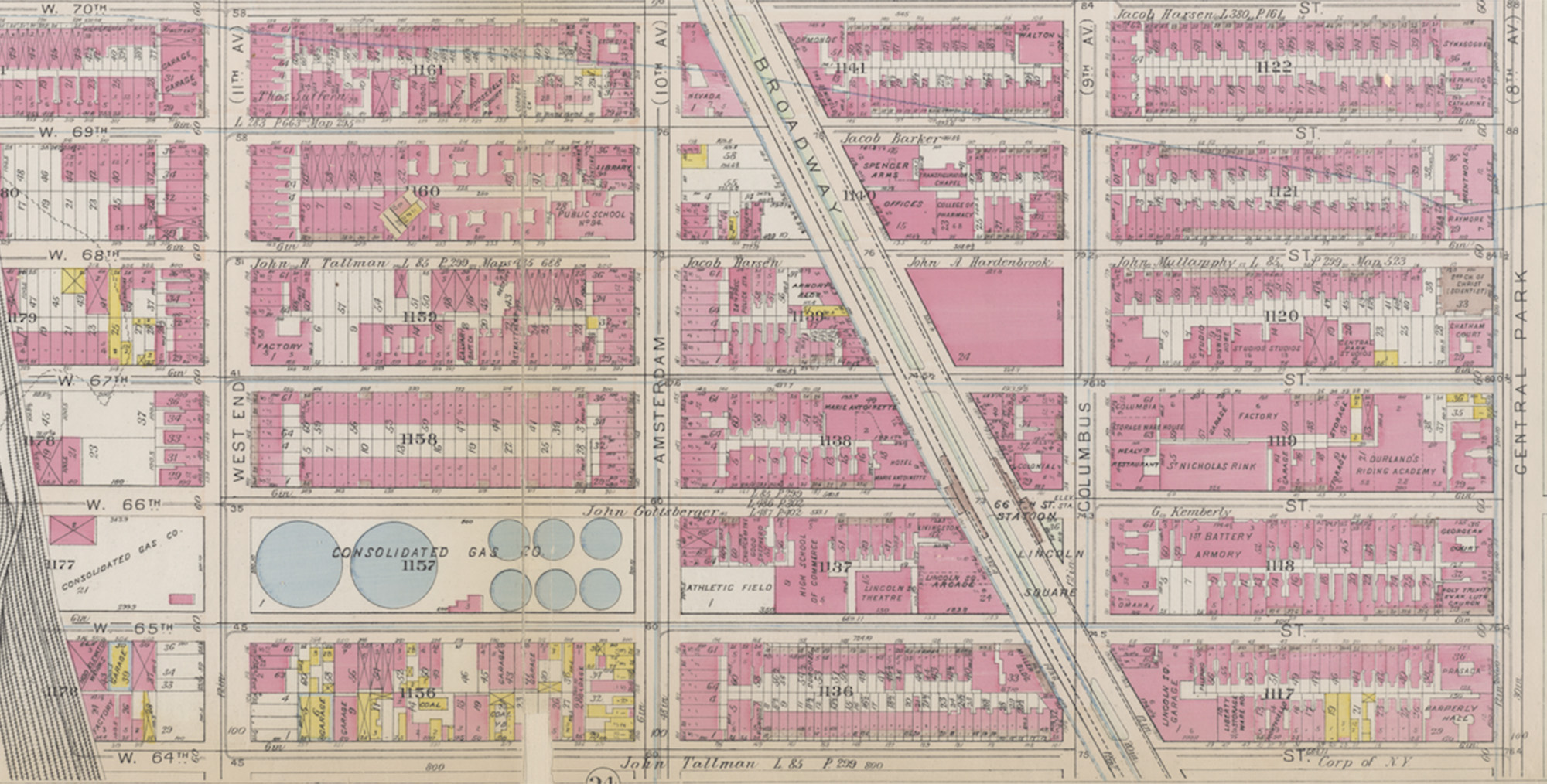

San Juan Hill, compact and densely populated, stretched from roughly West 60th to West 64th streets between Tenth and Eleventh avenues, today Amsterdam and West End avenues. Black Southerners and West Indians, and the rough and the respectable alike, lived jumbled together. To the west the open tracks of the New York Central Railroad formed a deadly hazard and the boundary of a hostile Irish neighborhood. Mary White Ovington, who helped found the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and lived for a time in San Juan Hill, described the area’s name and geography succinctly: “Whites dwelt on the avenues, colored on the streets, and fights between the two gave the hill its name.”4

In Tin Can Battle, San Juan Hill, New York, two groups of adolescents on a street just west and south of the Lincoln Arcade hurl cans at each other. The most clearly depicted of the combatants are Black and they have already routed two opponents, whose faces are turned away from us. The Black youth closest to us is primed for action, staring hard at his adversary. Black residents look on impassively from the far side of the street. Either this is a routine occurrence on this block or the outcome of the clash is not in doubt.

In Both Members of This Club, inspired by bouts that Bellows attended at Sharkey’s, the ringside crowd is howling. Two boxers, one Black and one white, are locked in the middle of the ring. The Black fighter surges forward as his white opponent starts to drop to the canvas. The white fighter—his face bloodied, his right leg buckling, and his arm and torso smeared with his own gore—is about to go down. Members of the crowd look on with shock, glee, enthusiasm, and grim fascination.

Bellows was enthralled by struggle—between individuals at sporting events and between individuals and the urban environment. And there was much struggle to be found in San Juan Hill. Migration to New York City offered Black people a chance at a better life, but they had to fight for everything they achieved—at work, in their neighborhood, and in the boxing ring.5

Bellows’ life and work help us understand San Juan Hill, how Bellows made memorable art there, and the history of male violence in the neighborhood. Equally important, they open up perceptions of the relationship between Manhattan’s West Side and the larger world. In the early 1900s, when Bellows was painting in San Juan Hill, events that he observed there resonated powerfully with developments in the city and the United States: white anxiety nationwide over the rise of Black heavyweight champion Jack Johnson and what his ascent meant for white supremacy; the transformation of prize fighting from a shadowy activity of uncertain legality to a legal commercial enterprise marketed to mass audiences; and the birth of Harlem as a Black neighborhood.

The geography of Black Manhattan in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was an archipelago, with islands of Black blocks in a larger sea of white residents. Black people might dominate certain streets, but white people were all around them.

Tensions over housing, jobs and policing inflamed relations between Black and Irish residents. Police were hostile to Blacks and inclined to side with whites. All parties carried grudges from both day-to-day encounters and memories of the Tenderloin riot of August 1900, in streets just south of San Juan Hill that were home to Irish and Black residents and a vice scene. For two days there after a Black man mortally wounded a policeman in plainclothes whom he thought was harassing his girlfriend, whites swarmed through the streets, beating African Americans. Police officers joined in the attacks or stood by.6

In 1905, what became known as the Battle of San Juan Hill began with an act of kindness on a hot July day, when a Black man agreed to escort a Jewish peddler through the neighborhood to protect him from local white youths. The youths attacked anyway. The Black man fought back, whites piled on, Blacks responded, and a battle was on. Police surged into the neighborhood and were pelted with bricks and bottles. They responded with nightsticks and brutality. Violence surged and gunfire crackled. Police disarmed Blacks but not whites and forced Black prisoners to run a gauntlet in a police station.7

Protests afterward achieved only limited results. The New York Age, a Black-owned newspaper, concluded that Black residents of San Juan Hill were “mobbed by hoodlums, clubbed by the police and railroaded by the courts.”8

Bellows moved into the northeast edge of this district in 1906, just as he was beginning a swift ascent in the New York art world. He settled into the sky-lit studio 616 of the Lincoln Arcade at West 65th and Broadway, at the downtown end of the Lincoln Square intersection, which runs between 65th and 66th Streets where Broadway sharply intersects with Columbus Avenue. The Lincoln Arcade, opened in 1903, was a six-story commercial building with an eclectic range of enterprises (among them a candy store, a barber and a pool hall), a heterogenous mix of tenants who were either on their way up or on their way down, and artists’ studios. A theatre stood around the corner on West 65th Street. Across Broadway at 127-129 Columbus Avenue was a boxing venue, Sharkey’s Athletic Club, run by the former heavyweight boxer Tom Sharkey. Sharkey’s neighbors included a dancing academy, a roller-skating rink that catered exclusively to African Americans, and a Democratic political club.9

Living and working at the Lincoln Arcade (with the young playwright Eugene O’Neill), Bellows was in the bohemian quarter of the West Side and a short walk from Black Manhattan. His drawing Tin Can Battle, San Juan Hill illuminates the violence between young men that was part of life in local streets: fierce and acted out at close quarters. This is a grim gang fight on a battered street, devoid of the color and sensationalism that animate Herbert Asbury’s influential book The Gangs of New York, which came out in 1928. It also is probably closer than Asbury to the everyday reality of San Juan Hill.10

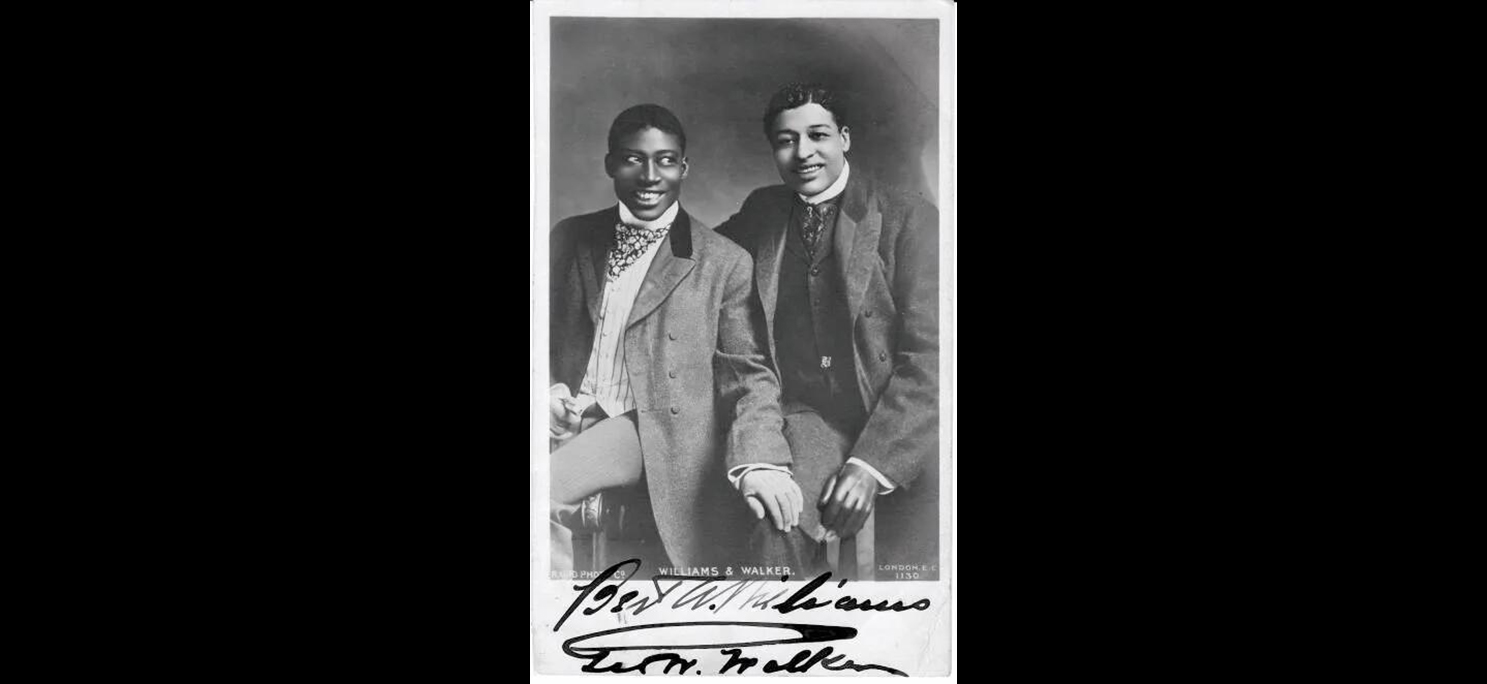

Bellows achieved greater fame from boxing paintings inspired by events closer to the Lincoln Arcade, at the Sharkey Athletic Club. When Bellows executed these works, boxing was in the middle of a halting evolution from an illegal activity conducted on the margins of polite society in the nineteenth century to a legal commercial enterprise in the twentieth. By the time Bellows was settled into the Lincoln Arcade, amateur boxing in gymnasiums was extolled by figures such as Theodore Roosevelt as the proper way to develop muscular masculinity, but in New York prize fighting for money was confined to “clubs” like Sharkey’s where patrons and pugilists alike were members. Bellows, an accomplished baseball player with an appreciation for the human body, physical action, and struggle, watched bouts at Sharkey’s and then in a studio painted what he remembered. At least once in 1910, Sharkey’s featured Black fighters.11

Both Members of This Club depicts a boxing match as a ferocious collision between two fighters, one Black and one white, straining against each other in front of an impassioned crowd. This is boxing as a slugging match, with no hint of a “sweet science”. The light is on the white fighter, whose right leg is buckling. It is easy to imagine him dropping to the canvas. The struggle captured in the painting resonates with both the race riots that took place only blocks from Sharkey’s and the wider anxiety among whites over the ascendance of Jack Johnson, who in 1908 became the first Black heavyweight champion of the world.12

Bellows’ own views on Black fighters are at best ambiguous: his original titles used a racist term for Blacks, but he later changed them to the titles that are used today. In an era when white fear of being dominated by Blacks was widespread, Both Members of This Club could indeed be interpreted as a representation of a Black body that inspires white fears. Yet unlike other white men who were roused to murderous fury at the thought of a victorious Black boxer, in an age when the United States Congress passed a law forbidding the showing of motion pictures of prizefights in order to block public depictions of Johnson’s victory, Bellows—always fascinated with conflict—portrays a Black fighter’s strength and a white fighter’s trouncing. And the title Bellows eventually chose for the painting, Both Members of This Club, suggests not only fight club practices of his day but the fact that both fighters shared a fraternity as combatants in the ring.13

What was not ambiguous was the reaction of white New Yorkers when the kind of contest represented in Bellows’ painting came to life. In July 1910, Jack Johnson, the first black heavyweight champion of the world, inflicted a humiliating defeat on Jim Jeffries, a former white champion who came out of retirement to challenge Johnson in a bout held in Reno, Nevada.14

When news of Johnson’s victory spread, whites attacked Blacks across the United States. In New York, gangs stalked the city assaulting Black people; one man was almost lynched. The New York Evening Post reported “a state of terror in San Juan Hill.” A white gang beat a Black man from the neighborhood so severely that his skull was fractured; he was saved by a doctor who protected him at gunpoint.15

The year 1910 would be Bellows’ last year at the Lincoln Arcade. In August, he bought a rowhouse on East 19th Street and installed a studio on the fourth floor. He continued to do drawings of boxers, including one that suggested the victorious Johnson. Another, a depiction of an exhausted white fighter between rounds titled The Savior of His Race, suggested Bellows’ skepticism about great white hopes. When he next rendered a prizefight in oil paint, it was Dempsey and Firpo, capturing a fight staged for a mass audience under bright lights at the Polo Grounds in upper Manhattan in 1923, when professional boxing had become a fully legal and regulated sport in New York State. In every respect, it is a long way from Sharkey’s.16

For Black New Yorkers, the year 1910 marked a turning point in the history of San Juan Hill. Not only were the tenements there overcrowded, but the vulnerability of a Black enclave on the West Side was revealed again in the attacks that followed the Jack Johnson victory. While San Juan Hill would retain Black residents, in the years after 1910 Black movement up the West Side would bring people of African descent to Harlem, a neighborhood with better housing stock, in transforming numbers.

In Harlem, Black people eventually built a majority that made them less vulnerable to white attacks. Racism and economic inequality afflicted them there as well, and Black people who sought housing further afield in northern Manhattan had to struggle to gain homes, but the vulnerability to gang violence that was a painful part of life in San Juan Hill was less of a problem in Harlem. Secure in their growing presence in Harlem, Black residents launched the cultural and political outpouring that would become known as the Harlem Renaissance. To be sure, discrimination and police violence were enduring problems in Harlem, and produced rioting there in 1935. Still, in the face of many injustices, Black New Yorkers turned Harlem into the global capital of the African diaspora.

When Johnson defeated Jeffries in 1910, white men hunted Black men in the streets of San Juan Hill. In 1937, when Joe Louis, “The Brown Bomber,” defeated James J. Braddock to win the heavyweight championship, crowds of joyous Black people in Harlem took to the streets in jubilation.17

Bellows did not live to see the celebration. He died from a ruptured appendix in 1925 at the age of 42. In a distinguished career that was cut short by an early death, his boxing paintings remain among his most acclaimed works. Boxer Tom Sharkey, who staged the bouts that inspired Bellows, eventually fell on hard times. He moved to California and died there in 1953, working as a racetrack security guard.18

Slightly longer lived were the Lincoln Arcade and San Juan Hill. The Lincoln Arcade (damaged but rebuilt after a fire in 1931), became a great incubator of artists. Its rambling facilities provided artistic homes for people as different as Henri (who taught there from 1910 to 1912), the playwright Eugene O’Neill, the critic Helen Appleton Read, and the artists Thomas Hart Benton, Marcel Duchamp, and Raphael Soyer. San Juan Hill remained a heterogeneous neighborhood with a strong African American presence and a reputation for being the home of important jazz musicians.19

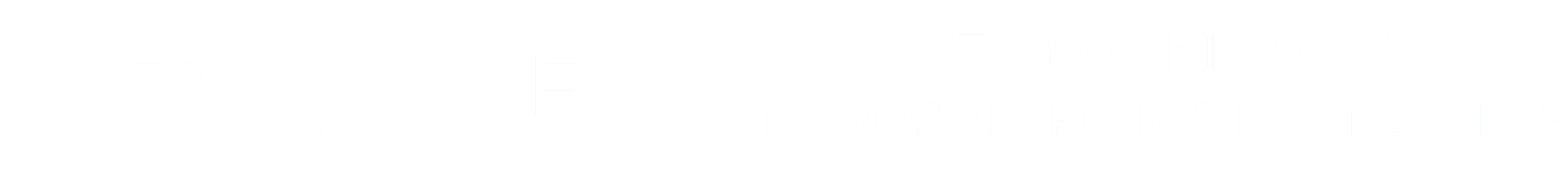

Both the Lincoln Arcade and the blocks surrounding it were demolished in the urban renewal project that produced Lincoln Center. Long afterward, in jazz numbers like James P. Johnson’s “Charleston” and Bellows’ boxing paintings, we can still sense the fierceness and beauty inspired by life around old Lincoln Square.

Notes

1 My knowledge of the Ashcan Artists is grounded in Rebecca Zurier, Robert W. Snyder and Virginia Mecklenburg, Metropolitan Lives: The Ashcan Artists and Their New York (Washington, D.C: National Museum of American Art/W.W. Norton, 1995). This essay was strengthened by advice from Rebecca, Elliott Gorn, Peter Eisenstadt, Dan Czitrom, Arlene Schulman and Clara Hemphill.

2 Both Members of This Club, 1909, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. and Tin Can Battle, San Juan Hill, New York, 1907. Sheldon Museum of Art, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Lincoln, Nebraska.

3 Marcy S. Sacks, Before Harlem: The Black Experience in New York City Before World War I (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006), 5-6.

4 Mary White Ovington, Black and White Sat Down Together: The Reminiscences of an NAACP Founder, edited and with a foreword by Ralph E. Luker, afterword by Carolyn E. Wedin (New York: The Feminist Press at the City University of New York, 1995), 26. On Black life in San Juan Hill, especially the lives of women, see Saidiya Hartman, Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval (New York: W.W. Norton, 2019), 180-83, 220-25. On neighborhoods, boundaries, gangs and the Irish in American cities in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, see James R. Barrett and David R. Roediger, “The Irish and the ‘Americanization’ of the ‘New Immigrants’ in the Streets and in the Churches of The Urban United States, 1900-1930,” Journal of American Ethnic History, Summer 2005, Vol. 24, No. 4, 7-11, 13-16.

5 Edward Wolner, “George Bellows, Georg Simmel, and Modernizing New York,“ American Art, Vol. 29, No. 1 (Spring 2015), 108, 113; and Sacks, Before Harlem, 3-7.

6 Sacks, Before Harlem, 5-7, 79-81; Hartman, Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments, 258-59; Marilynn Johnson, Street Justice: A History of Police Violence in New York City (Boston: Beacon Press, 2003), 57-58, 60-69, 80-81 and Gilbert Osofsky, Harlem: The Making of a Ghetto, Negro New York, 1890-1930 (New York: Harper and Row, 1963), 46-49.

7 Johnson, Street Justice, 80-85; Sacks, Before Harlem, 80-82; and “Black and White War in a Crowded District,” New York Times, July 15, 1905, 1 and “Race Rioters At it Again,” New York Times, July 18, 1905, 1.

8“ Race Riots in New York,” The New York Age, July 13, 1905, 4.

9 Tom Miller, “127-129 Columbus Avenue,” https://www.landmarkwest.org/boulevard-encore/127-129-columbus-avenue/.

10 Zander Brietzke, “Eugene O’Neill, George Bellows and the Lincoln Arcade,” Eugene O’Neill Review, 2021-03, V. 42 (1), 17-18; Peter Salwen, Upper West Side Story: A History and Guide (New York: Abbeville Press, 1989), 202; and Owen Johnson, “Owen Johnson Discovers a New Bohemia Here,” New York Times, October 22, 1916, SM9.

11 Pamela Cooper, “boxing,” Peter Eisenstadt, editor, The Encyclopedia of New York State (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2005), 201-202; “Williams Knocked Out,” New York Times, June 16, 1910, 11.

12 Geoffrey C. Ward, Unforgivable Blackness: The Rise and Fall of Jack Johnson (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2004), 122-33, 162-63, 200-205.

13 Martin A. Berger, “George Bellows and the Complication of Race” in M. Melissa Wolfe, George Bellows Revisited: New Considerations of the Painter’s Oeuvre (Newcastle upon Tyne, UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing), 76-78; and Gail Bederman, Manliness and Civilization: A Cultural History of Gender and Race in the United States, 1880-1917 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995), 1-3; and Rachel Schreiber, “George Bellows’s Boxers in Print,” The Journal of Modern Periodical Studies (Volume 1, number 2, 2010), 165.

14 Ward, Unforgivable Blackness, 208-11.

15 “Race riots in dozen cities follow Johnson fight victory,” UPI Archives, July 5, 1910, https://www.upi.com/Archives/1910/07/05/Race-riots-in-dozen-cities-follow-Johnson-fight-victory/8746818371120/; “Eight Killed in Fight Riots,” New York Times, July 5, 1910, 1; and “Negroes Attacked in This City,” New York Evening Post, July 5, 1910, 3.

16 Schreiber, “George Bellows’s Boxers in Print,” 159-161, and Elliott J. Gorn, The Manly Art: Bare-Knuckle Prize Fighting in America (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1986), 248-54.

17 “Negroes’ Joy Unrestrained As Louis Wins,” Washington Post, June 23, 1937, 22.

18 Charles Brock, “George Bellows: An Unfinished Life” in Charles Brock, editor, George Bellows (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 2012), 7; and Jim Shanahan, “Sharkey, Thomas Joseph,” Dictionary of Irish Biography, https://www.dib.ie/biography/sharkey-thomas-joseph-tom-sailor-a7995.

19 Robin D.G. Kelley, Thelonious Monk: The Life and Times of an American Original (New York: Free Press, 2010), 23-27; Seton Hawkins, “San Juan Hill and the Black Music Revolution,” Legacies of San Juan Hill, https://lincolncenter.org/feature/legacies-of-san-juan-hill/san-juan-hill-and-the-black-music-revolution; and Samuel Zipp, Manhattan Projects: The Rise and Fall of Urban Renewal in Cold War New York (New York: Oxford, 2010), 197-98.