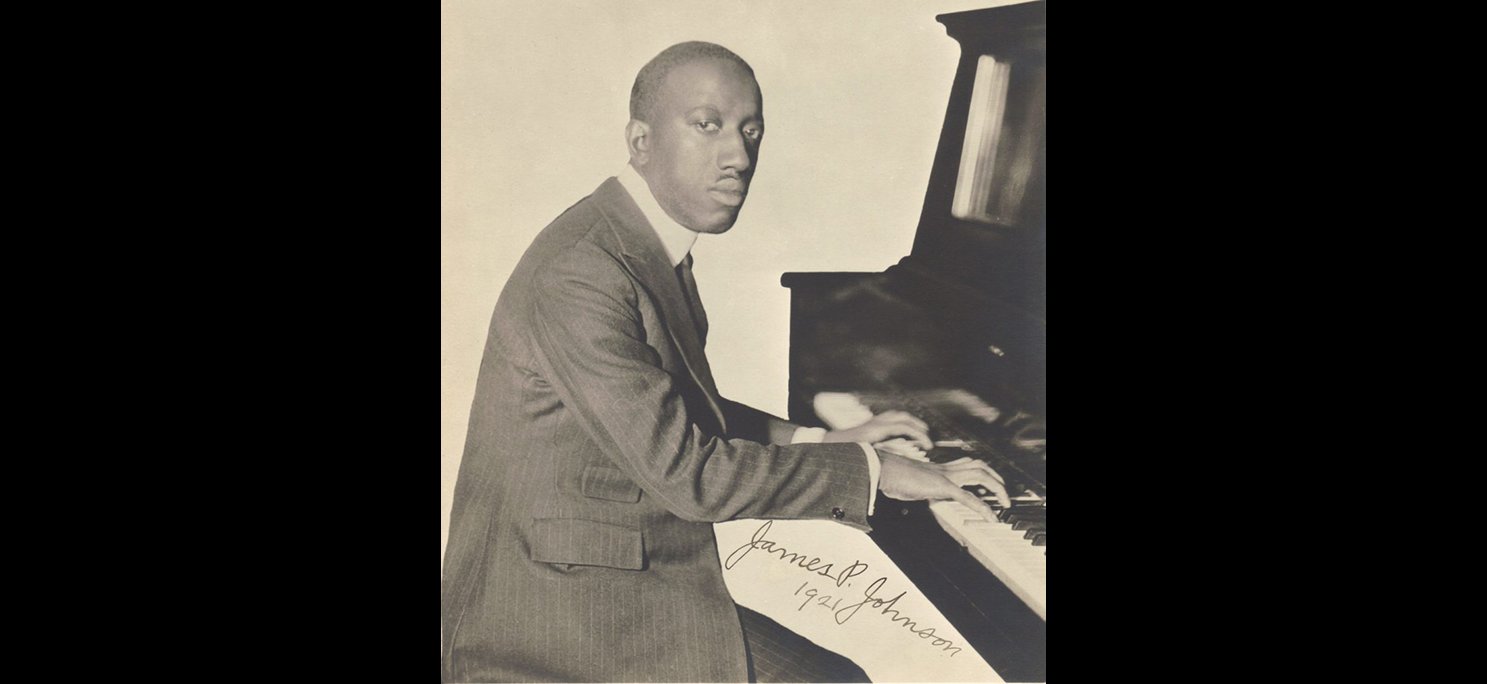

James P. Johnson, 1921

Courtesy of Scott E. Brown

—James Weldon Johnson, The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man (1912)

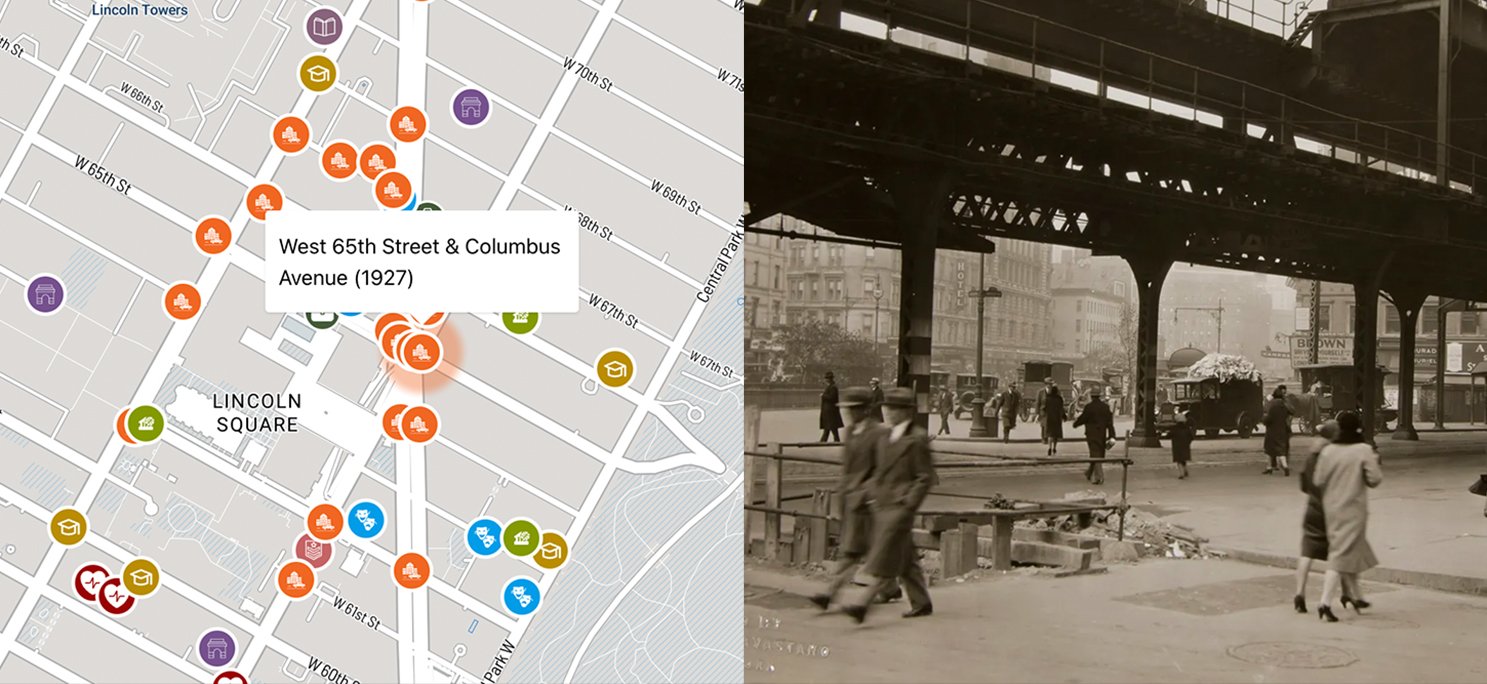

In 1908, James P. Johnson, along with his mother, stepfather, two of his stepbrothers, his late stepsister’s daughter, and his surviving stepsister, moved from Jersey City to 152 West 62nd Street, in Manhattan’s San Juan Hill neighborhood. Johnson was fourteen years old. His new home was relatively recent, a Renaissance Revival-style apartment block built in 1899.1 Johnson and his family shared the building with thirteen other households, all of them African-American or West Indian. That was increasingly typical of the neighborhood, which had, in a few short years, filled up with Black migrants.

The press was already calling the area San Juan Hill. Whether it was because of the local preponderance of Black veterans of the Spanish-American War—and its famous Battle of San Juan Hill—or because of the area’s violent clashes between Black newcomers and their white immigrant neighbors, nobody could say.2 Maybe it was both, depending on who was talking about it, and why. Certainly the place teemed with aspiration and unrest in equal measure.

Black residents had their own name for the neighborhood: the Jungles. “It was the toughest part of New York,” Johnson said. “There were two to three killings a night.”3 But it was also a teeming cauldron of musical possibility, with residents eager for novelty and musicians in furious competition to innovate. Johnson, already envisaging a career in music, considered his new apartment a definite step up. For one thing, there was room for a piano.

Born in New Brunswick in 1894, Johnson first learned piano from his mother Josephine. As soon as he was tall enough to reach the keys, James started picking out tunes, with his mother’s help. He was and would always be a quick study, with perfect pitch and a perfectionist’s persistence. But they sold the piano when the family moved to Jersey City.

A busy port and railroad hub, Jersey City saw millions of visitors every year, looking for opportunity, for escape, for a good time. Johnson’s older brother frequented sporting houses and saloons; Johnson, still in short pants, would tag along, listening at the door. He became especially fascinated by the piano players—“ticklers,” decorating popular songs of the day with ragtime syncopations. They were, more often than not, small-time criminals as well. But Johnson was beguiled by their charisma, their sharp clothes, their talent. “They were popular fellows, real celebrities. They had lots of girl friends, led a sporting life and were invited everywhere there was a piano. I thought it was a fine way to live.”4

But Johnson was also picking up music at home, from his neighbors—southern Black residents, for the most part, who had come north as part of the Great Migration. “The northern towns had a hold-over of the old southern customs,” Johnson remembered.

"I’d wake up as a child and hear an old-fashioned ring-shout going on downstairs…. They danced around in a shuffle and then they would shove a man or a woman out into the center and clap hands. This would go on all night and I would fall asleep sitting at the top of the stairs in the dark."5

The experience would bear musical fruit in the Jungles.

“I never heard real ragtime until we came to New York,” Johnson said.6 The ticklers in Jersey City had jumped on the ragtime bandwagon, but the pianists in Manhattan were on a different level. A friend named Charlie Cherry tutored Johnson through some of Scott Joplin’s rags (“First he played, then I copied him, and then he corrected me”), giving Johnson the foundation on which other New York pianists were already building.7 Ragtime’s lilt would, in the crucible of the Jungles, become something galvanic.

In the meantime, Johnson was reconnoitering another tradition crucial to the New York style: European classicism. At P.S. 69, Johnson played piano for assemblies and sang in the choir. Johnson remembered being recruited by Frank Damrosch, Walter’s brother—the progressive, democratically-minded Damrosch habitually beefed up his already large People’s Choral Union with an additional boys’ chorus for performances.8 Johnson began to absorb orchestral literature via the New York Philharmonic at Carnegie Hall; a brother’s friend waited tables at a restaurant frequented by conductor Josef Stransky, who tipped with free tickets.

Such concerts were at a remove from San Juan Hill, geographically and culturally. But they left their mark on the music being made there. Immigrants brought classical music to New York, and New Yorkers came to expect its polish and virtuosity. “The people in New York were used to hearing good piano played in concerts and cafes,” Johnson said.

"The ragtime player had to live up to that standard. They had to get orchestral effects, sound harmonies, chords and all the techniques of European concert pianists who were playing their music all over the city."9

In 1911, Johnson and his family moved uptown, to West 99th Street, a small but vibrant Black enclave. (Among his new neighbors were composer and actor J. Rosamond Johnson, who, with his brother James Weldon Johnson, had mounted successful operettas, and composer Will Marion Cook, whose 1903 In Dahomey was the first all-Black production on Broadway; Johnson would later count both as colleagues.)10 Johnson took his first professional jobs, in Far Rockaway, in Jersey City, in the Tenderloin, near midtown. It’s as if he was circling his way back to the center of his ambitions: the Jungles. Before long, he was working—and, once again, living—in San Juan Hill.11

Back in his old neighborhood, around 1913, Johnson landed gigs in two basements. Jim Allan’s, at 61st and 10th, was a bar with a gambling room, where ragtime kept the atmosphere festive and the liquor flowing. The other place, on 62nd, fostered a more vigorous approach. Its official name was Drake’s Dancing Class—the veneer of instruction keeping the city’s zoning and licensing enforcement at bay—but everybody knew it as the Jungles Casino. It was dank and rundown. “[T]he rain used to flow down the walls,” recalled Willie “The Lion” Smith, Johnson’s great friend and rival. “It was so damp down there that they used to try to keep the piano dry by placing lit candles around it.”12 The clientele was Black migrants from up and down the Atlantic seaboard, from Georgia and the Carolinas, who mostly worked in the docks along the Hudson. They would do the set dances and ring-shouts, like Johnson had witnessed in Jersey City, but with more abandon and zeal. As Johnson described it:

"These Charleston people and the other southerners had just come to New York. They were country people and they felt homesick. When they got tired of two-steps and schottisches..., they'd yell: “Let's go back home!”… Breakdown music was the best for such sets, the more solid and groovy the better. They'd dance, hollering and screaming until they were cooked."3

The ring-shouts had originated in church, the set dances in parlors, but the “breakdown music” was new, with Johnson drawing on his ragtime prowess to meet such moments. The old-timers frowned; the younger patrons exulted. But traditional ragtime couldn’t cut through the commotion. Inspired by the music that surrounded them in Manhattan, Johnson and the other pianists beefed up their sound. Accents shifted to the backbeat. The right-hand melodies were filled out with rich harmonies and double-notes and ringing clusters. The left hand became a locus of innovation: thumping octaves, rolling tenths, the line breaking up into volcanic, relentless boogie-woogie rumbles.14 Most important was the rhythm, the drive. The syncopations that decorated ragtime’s surface now became the generating force, fueling the all-night ritual.

During the day, however, Johnson honed his technique. He began studying classical repertoire with Bruto Giannini, an Italian-born composer, conductor, and pianist who also taught Scott Joplin. Johnson worked through Bach and Beethoven, Chopin and Liszt. Giannini also tutored Johnson in composition and theory, quite possibly encouraging Johnson to use the styles and sounds he encountered in the dance halls as compositional fodder.15

One hears it in Johnson’s most celebrated composition from this period, his calling card. “Carolina Shout” is, at its heart, just that: a ring-shout, danced by the migrants from the Carolinas, a number typical of a given night at the Jungles Casino, complete with flashy, improvised ragtime embellishment. But the music’s demands, the shifting, leaping left hand, the fistfuls of notes in the right, the density of breaks and flourishes—the formidable hurdles that made the piece the standard entrance exam for New York pianists throughout the 1920s—echo the most athletic Romantic virtuosi.

At this time, jazz as we think of it, as a distinct style, as a genre, did not yet exist. What Johnson was hearing and creating in the Jungles was, rather, a collision of styles and ideas, peculiar to the place and time. The ticklers’ embrace of the ragtime fad; the exhilaration of the Black migrants’ hometown dances; the European classical virtues of grandeur and technical brilliance—Johnson would synthesize it all into something new, expansive enough to warrant its own name.

The same boom-and-bust real estate market that made San Juan Hill so attractive and affordable to newcomers soon put another neighborhood within reach: Harlem. By the 1920s, it supplanted the Jungles. (Johnson’s various addresses during this period parallel the shift north: West 59th, West 64th, Lenox Ave., West 141st.16)

In the Jungles, Johnson was a contender; in Harlem, he reigned. His tickler’s flair, his exacting ear, his work ethic, his omnivorous imagination, and his eager competitive streak guaranteed it. In clubs, at rent parties, wherever two or more pianists gathered in the name of showing off, Johnson trounced all comers. (It was only in 1932, at a high-level summit at Morgan’s Bar in Harlem—the other contestants were Willie “The Lion” Smith and Johnson’s protege, Thomas “Fats” Waller—that Johnson ceded his crown, to a newcomer named Art Tatum.17)

At crucial points in his career, though, Johnson would continue to mine the distilled, stylized vein of southern folklore he encountered and transfigured in the Jungles. There was “Carolina Shout,” of course, his signature, his Excalibur in the cut-and-thrust of pianistic battle. But, also, “The Charleston,” Johnson’s greatest hit as a theatrical songwriter, a reworking of the best of the themes he had invented to accompany the dancers at Jim Allan’s and Drake’s Dancing Class. (Runnin’ Wild, the show that launched “The Charleston” into the zeitgeist, premiered at the Colonial Theater, less than two blocks from Johnson’s old 62nd Street tenement.) Johnson’s aspirations toward classical and orchestral composition would first bear fruit with the piano rhapsody Yamekraw, named for and evoking a Black settlement on the outskirts of Savannah.

Still, for all its energy, San Juan Hill was the center of Black life in Manhattan for only a decade or so, maybe two. It was Harlem that had a renaissance. It was Harlem that gave its name to the dazzling piano style that Johnson pioneered and exemplified: Harlem stride. Stride begat swing, swing begat bebop, and, by mid-century, jazz garnered the sort of critical and intellectual and historical attention that classical music had long enjoyed. But its beating heart was still the principles Johnson had distilled out of the welter of the Jungles: northern swagger, southern strut, and classical splendor. Features became tenets. A century later, the sound of jazz is still, on some level, the sound of San Juan Hill.

Notes

1 The building was designed and built by Frederick C. Zobel, a German immigrant who would, along with his brothers, go on to become one of the city’s most well-known real estate developers. Today the site is occupied by Fordham University’s McKeon Hall.

2 In a 1908 adventure of Old and Young King Brady, fictional Secret Service agents whose weekly exploits were dime‑novel staples, the origin defeated even those sleuths: “This peculiar name has attached itself to the largest of New York’s several colored quarters, for some reason which we could never learn.” Secret Service: Old and Young King Brady, Detectives, no. 476 (March 6, 1908), p. 1.

3 Tom Davin, “Conversations with James P. Johnson [II], 1912–14.” The Jazz Review, vol. 2, no. 6 (July 1959), p. 11.

4 Davin, “Conversations with James P. Johnson [I].” The Jazz Review, vol. 2, no. 5 (June 1959), p. 16.

5 Rudi Blesh and Harriet Janis, They All Played Ragtime (4th ed.; New York: Oak Publications, 1971), p. 190.

6 Davin, “Conversations [I],” p. 17.

7 Ibid. Presumably Cherry played piano in some professional capacity—later New York City directories (1917 and 1925) list a “Cherry, Chas—musician” at Harlem addresses—but, like many such pianists of the generation before Johnson, he left little other historical trace. In fact, the few mentions of Cherry in the record seem to originate with Johnson (beginning with n.a., “Jimmie,” Time vol. XLII no. 26 (December 27, 1943)). The 1915 New York State Census has a “Chas Cherry,” home address 135 Lenox Ave., listed as an inmate of the Blackwell’s Island Penitentiary—one wonders if the sporting life temporarily caught up with Johnson’s mentor.

8 Ibid. The exact concert Johnson was referring to is unclear, but his recollection of the repertoire (Haydn’s Creation) and his receiving of a bronze medal for his participation strongly suggest that it was the gala concert Damrosch mounted at Carnegie Hall on October 3, 1909, as part of the citywide Hudson-Fulton Celebration.

9 Ibid.

10 J. Rosamond Johnson contributed choral arrangements to the 1929 short film St. Louis Blues (starring Bessie Smith) and the 1933 film adaptation of The Emperor Jones, both of which also featured James P. Johnson on piano; as Johnson’s ambitions took him more and more into the concert hall, he and J. Rosamond would appear more than once on the same program. Will Marion Cook, meanwhile, would conduct and/or co-write several of Johnson’s musicals. Cook also was the witness on Johnson’s passport application.

11 It’s not known exactly when Johnson moved back to San Juan Hill, but, by 1915, he was living on 344 W. 59th Street with his mother. Interestingly, the New York state census listed both of their occupations as “Musician.”

12 Willie “The Lion” Smith with George Hoefer, Music on My Mind: The Memoirs of an American Pianist (Garden City: Doubleday, 1964), p. 65.

13 Davin, “Conversations [II],” p. 12.

14 Otto “Toby” Hardwicke, longtime saxophonist in the Ellington band who also performed frequently with “Fats” Waller, attributed stride’s advanced left-hand technique to more lubricative concerns: “[E]verybody wanted to treat the piano player. Drinks were lined up ten deep all night long… and to keep the ball rolling, the box-beater had to reach for a drink with his right hand and keep the melody going with his left. That’s how left-hands were born!” Inez M. Cavanaugh, “Reminiscing in Tempo,” Metronome (November 1944), p. 17.

15 For an exhaustive overview of Giannini’s career and influence, see Marcello Piras, “Garibaldi to Syncopation: Bruto Giannini and the Curious Case of Scott Joplin’s Magnetic Rag,” Journal of Jazz Studies vol. 9, no. 2 (Winter 2013), pp. 107–177. Given their shared teacher, Johnson’s devotion to Joplin’s rags, and their occasional appearances at the same venue (Barron Wilkins’ Little Savoy club, for instance), it seems almost inconceivable that Johnson and Joplin weren’t at least acquaintances, yet there is no record of them ever meeting.

16 To be exact: after Johnson’s 59th Street address in 1915, there was 214 W. 64th Street (1918, from Johnson’s draft registration); 673 Lenox Ave. (1921, from Johnson’s passport application); 269 W. 141st Street (1923, from the passenger list of the S.S. Cedric, returning to New York from Liverpool on May 27 of that year). By 1930, Johnson had settled in Jamaica, Queens, at 171-38 108th Ave. It would remain his home for the rest of his life. Special thanks to James P. Johnson biographer Scott E. Brown for his help in untangling the chronology.

17 Maurice Waller and Anthony Calabrese, Fats Waller (New York: Schirmer Books, 1977), pp. 97–98. According to Waller, Johnson’s opening salvo was, naturally, “Carolina Shout,” but his closing argument was a stride version of Chopin’s “Revolutionary” Étude, op. 10, no. 12.