William P. Gottlieb/Ira and Leonore S. Gershwin Fund Collection, Music Division, Library of Congress.

English

Spanish

San Juan Hill and the Black Music Revolution

San Juan Hill y la revolución de la música negra

January 30, 2023

by Seton Hawkins, Director of Public Programs and Education Resources at Jazz at Lincoln Center

Para muchos amantes de la música de hoy, la asociación del histórico San Juan Hill con la innovación musical queda relegada, en gran medida, a su papel como trasfondo de la guerra de bandas ficticia de West Side Story. Si le pedimos a un amante del jazz que describa los lugares clave de la ciudad de Nueva York para la innovación del jazz, seguramente nos hablará de Harlem, Swing Street y el Village. ¿Pero qué pasa con San Juan Hill? La idea de que el actual emplazamiento del Lincoln Center fue, en otros tiempos, un semillero de revoluciones artísticas en la cultura popular podría suscitar miradas de perplejidad y, sin embargo, la rica historia de logros artísticos, colaboraciones musicales y obras de genialidad de los negros de este barrio se sigue sintiendo hasta la actualidad. Aunque eclipsada por el Renacimiento de Harlem, la cultura musical de San Juan Hill contribuyó, en última instancia, a dar forma a las innovaciones de su vecino del norte.

San Juan Hill helped reshape the trajectory of Black music in America.

San Juan Hill contribuyó a reconfigurar la trayectoria de la música negra en los Estados Unidos.

As the United States rang in the 20th century, San Juan Hill was poised to become the most densely populated space within Manhattan as well as home to most of the city’s Black residents. While ostensibly integrated—African-American families from the South, Puerto Rican families, European immigrants as well as Caribbean immigrants all lived in the area—the neighborhood was nevertheless segregated by street. While it became infamous in the press for racial violence and unrest (and many jazz musicians from the neighborhood recount stories of fights both amusing and harrowing), it also became a place of intense cohesion for communities. As families firmed their roots in the neighborhood, extended family and friends soon joined them. Indeed, of the 60,000 Black residents living in New York City by 1902, more than half had moved there, most traveling from the American South and some emigrating from the Caribbean.1 Arriving to difficult living conditions and wages that were frequently nowhere near as lucrative as promised, the incoming residents also found themselves in the epicenter of a musical explosion. The popular music revolution of the 20th century was already humming along confidently thanks to a rich and robust artistic foundation laid by New York City’s Black artists in the 19th century.

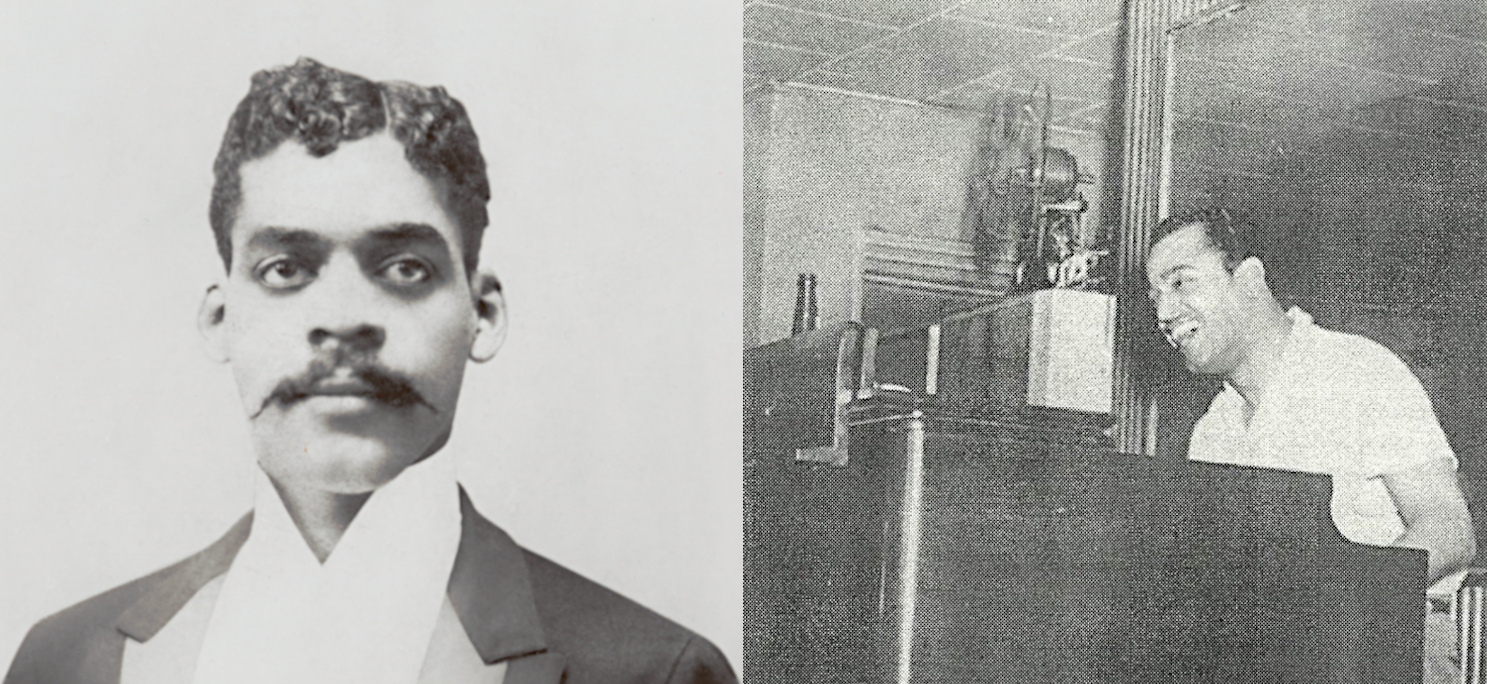

The early 20th century saw both jazz and the New Orleans artists who mastered it spreading out around the country, and as they came to New York City they folded into an extraordinary array of music already surging within Manhattan. Thanks to a number of brilliant performers, bandleaders, composers, and organizers, the burgeoning Black neighborhoods on the west side of Manhattan gave rise to a creative community known as “Black Bohemia.” Stage performers like Bert Williams and George Walker, writers including James Weldon Johnson, composers like Will Marion Cook and J. Rosamond Johnson, and bandleaders like the legendary James Reese Europe made up this scintillating assemblage of talents, who in turn centered their thrum of activity around the Marshall Hotel on 53rd street.2 Facing a highly segregated and exceedingly unequal landscape in show business, these artists developed an intensely organized and self-sufficient network amongst themselves, laying groundwork for artistic societies and guilds that helped ensure quality work for artists and advocate for appropriate pay for their ample talents. In spite of significant headwinds from a racist industry, James Reese Europe’s own Clef Club, officially inaugurated in 1910, would at its peak draw in $120,000 annually3 in revenue for artists ($3.4 million in 2021). This level of opportunity was not lost on the area’s residents, many of whom had been relegated to menial labor: by the early 20th century, music would serve as a crucial source of revenue for a large percentage of San Juan Hill’s residents.

The business acumen of these artists alone is worthy of mention and praise; that they also produced immortal works that would reshape popular music renders this all the more remarkable. From James Reese Europe’s iconic musical collaborations with the dancing team Vernon and Irene Castle, to Will Marion Cook and Paul Laurence Dunbar’s musical Clorindy, or The Origin of the Cake Walk, this early vanguard would lay a groundwork upon which later figures would build.

Significantly, this bedrock of achievement was laid in the decades prior to the Harlem Renaissance, and it serves as the backdrop for exploring San Juan Hill’s impact on the development of jazz. That the neighborhood rose in importance and population at the early 20th century and remained active until its mid-20th century demolition meant that its story runs in tandem with the development of jazz through its rise as popular music and ultimately into its continued evolutions in styles like bebop.

A comienzos del siglo XX, San Juan Hill estaba destinado a convertirse en el espacio más densamente poblado de Manhattan y en el hogar de la mayoría de los residentes negros de la ciudad. Si bien aparentemente lucía muy integrado -en la zona vivían familias afroamericanas del sur, puertorriqueñas, inmigrantes europeos y caribeños-, el barrio estaba segregado por calles. Aunque se hizo tristemente célebre en la prensa por la violencia y los disturbios raciales (y muchos músicos de jazz del barrio cuentan historias de peleas tan divertidas como angustiosas), también se convirtió en un lugar de intensa cohesión para las comunidades. A medida que las familias se arraigaban en el barrio, pronto se les unieron familiares y amigos. De hecho, de los 60,000 residentes negros que vivían en la ciudad de Nueva York en 1902, más de la mitad se habían trasladado allí, la mayoría procedentes del sur de los Estados Unidos y algunos emigrados del Caribe.1 Los residentes que llegaron se encontraron con condiciones de vida difíciles y salarios que, a menudo, no llegaban ni remotamente a ser tan lucrativos como se les había prometido, pero también se encontraron en el epicentro de una explosión musical. La revolución de la música popular del siglo XX ya latía con fuerza gracias a los ricos y sólidos cimientos artísticos que los artistas negros de la ciudad de Nueva York habían establecido en el siglo XIX.

A principios del siglo XX, tanto el jazz como los artistas de Nueva Orleans que lo interpretaban se dispersaron por todo el país, y al llegar a la ciudad de Nueva York, se sumaron a la extraordinaria variedad de estilos musicales que estaban surgiendo en Manhattan. Gracias a una serie de brillantes intérpretes, directores musicales, compositores y organizadores, los florecientes barrios negros del lado oeste de Manhattan dieron lugar a una comunidad creativa conocida como la “Bohemia Negra”. Intérpretes como Bert Williams y George Walker, escritores como James Weldon Johnson, compositores como Will Marion Cook y J. Rosamond Johnson, y directores musicales como el legendario James Reese Europe formaban este brillante conjunto de talentos, que a su vez centraban su actividad en torno al Marshall Hotel de 53rd Street.2 Frente a un panorama signado por la segregación y la desigualdad en el mundo del espectáculo, estos artistas desarrollaron una red muy organizada y autosuficiente entre ellos, sentando las bases de las sociedades artísticas y los gremios que ayudaron a garantizar un trabajo de calidad para los artistas y a abogar por una remuneración adecuada para sus vastos talentos. Pese a los importantes obstáculos de una industria racista, el propio Clef Club de James Reese Europe, inaugurado oficialmente en 1910, llegó a recaudar en su momento álgido $120,000 dólares anuales3 en ingresos para los artistas ($3.4 millones de dólares en 2021). Este nivel de oportunidades no pasó desapercibido para los residentes de la zona, muchos de los cuales habían sido relegados a labores serviles: a principios del siglo XX, la música serviría como una fuente crucial de ingresos para un amplio porcentaje de los residentes de San Juan Hill.

La perspicacia empresarial de estos artistas es por sí sola digna de mención y elogio; el hecho de que también produjeran obras inolvidables que transformarían la música popular lo hace aún más notable. Desde las emblemáticas colaboraciones musicales de James Reese Europe con la pareja de bailarines Vernon e Irene Castle, hasta el musical Clorindy, o The Origin of the Cake Walk, de Will Marion Cook y Paul Laurence Dunbar, esta primera vanguardia sentaría las bases sobre las que se sustentarían las figuras posteriores.

Es significativo que este cimiento de logros se haya establecido en las décadas anteriores al Renacimiento de Harlem, y que sirva de telón de fondo para explorar el impacto de San Juan Hill en el desarrollo del jazz. El hecho de que el barrio creciera en importancia y población a principios del siglo XX, y se mantuviera activo hasta su demolición a mediados del siglo XX, significa que su historia corre de forma paralela al desarrollo del jazz a través de su ascenso como música popular y, en última instancia, a sus continuas evoluciones en estilos como el bebop.

To be sure, the residents of San Juan Hill did not simply bear witness to the evolution of jazz; they were active architects in its development.

Sin duda, los residentes de San Juan Hill no se limitaron a ser testigos de la evolución del jazz; sino que fueron artífices activos de su desarrollo.

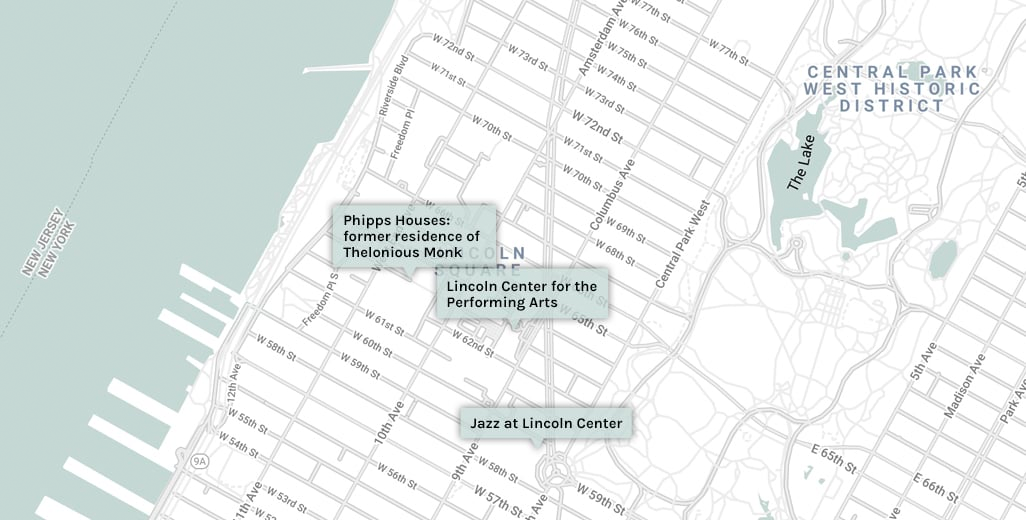

Generations of jazz musicians from James P. Johnson to Benny Carter to Thelonious Monk to Herbie Nichols called San Juan Hill home at some point in their lives. Their own stories illuminate the broader picture of Black art in America, and their experiences help to show how jazz developed throughout the century.

Generaciones de músicos de jazz, desde James P. Johnson hasta Benny Carter, pasando por Thelonious Monk y Herbie Nichols vivieron en San Juan Hill en algún momento de sus vidas. Sus propias historias ilustran el panorama más amplio del arte negro en los Estados Unidos, y sus experiencias ayudan a mostrar cómo se desarrolló el jazz a lo largo del siglo.

The eldest of the above artists, James P. Johnson, was himself a transplant to San Juan Hill, moving there with his family from New Jersey in 1908. While his time as a resident lasted only a few years, his engagement with San Juan Hill persisted into his professional career. This confluence of Johnson’s playing with the musical cultures of San Juan Hill would ultimately foment a revolution in the 1920s. Performing on West 62nd Street at what was officially called Drake’s Dancing Class—though better known within the neighborhood as The Jungles Casino4—throughout the 1910s, Johnson came face-to-face with the plethora of differing cultural heritages that made up the Black communities of San Juan Hill. Recounting his time performing for dancers at The Jungles, Johnson recalled a large portion of the clientele hailing from Charleston, South Carolina, who as he put it “danced hollering and screaming until they were cooked. They kept up all night or until their shoes wore off, most of them after a heavy day’s work on the docks.”5

The distinctive dances of these Charleston transplants would take on a crucial role in Johnson’s music. “‘The Charleston’ was a regulation cotillion step without a name,” he recalled. “While I was playing for these Southern dancers I composed a number of ‘Charlestons,’ eight in all.”

El mayor de los artistas mencionados, James P. Johnson, fue él mismo un inmigrante de San Juan Hill, que se trasladó allí con su familia desde Nueva Jersey en 1908. Aunque su estancia como residente duró solo unos pocos años, su compromiso con San Juan Hill persistió en su carrera profesional. Esta confluencia de la forma de tocar de Johnson con las culturas musicales de San Juan Hill acabaría fomentando una revolución en la década de 1920. Al presentarse en West 62nd Street en lo que oficialmente se llamaba Drake's Dancing Class -aunque era más conocido en el barrio como The Jungles Casino4—durante la década de 1910, Johnson se encontró cara a cara con la plétora de diferentes herencias culturales que conformaban las comunidades negras de San Juan Hill. Cuando interpretaba para los bailarines de The Jungles, Johnson recordaba que una gran parte de la clientela procedía de Charleston (Carolina del Sur) y que, según él, “bailaban a los gritos y chillaban hasta extenuarse. Seguían toda la noche o hasta que se les gastaban los zapatos, la mayoría de ellos después de un arduo día de trabajo en los muelles”.5

Los bailes característicos de los provenientes de Charleston asumirían un protagonismo crucial en la música de Johnson. “‘El charlestón’ era una especie de paso de cotillón sin nombre”, recordaba. “Mientras tocaba para estos bailarines sureños compuse varios ‘charlestones’, ocho en total”.

Drawing upon the now-iconic two-note rhythmic pulse of the dance, Johnson would compose music that perfectly encapsulates San Juan Hill’s unique impact: African in origin, preserved and carried through generations of Black families in the South, now brought together with the rising style of stride piano on the west side of Manhattan.

Basándose en el ya icónico pulso rítmico de dos notas de la danza, Johnson compondría una música que compendia perfectamente el impacto único de San Juan Hill: De origen africano, conservada y llevada a través de generaciones de familias negras en el Sur, ahora reunida con el estilo ascendente del stride piano en el lado oeste de Manhattan.

“Charleston” is a work at once deeply traditional and extraordinarily modern. That it would become virtually synonymous with popular dance in the 1920s speaks to just how deeply indebted American popular culture is to African-American traditions.

While the music of the Charleston highlights for us the varied cultural practices of the many newcomers to San Juan Hill, the spread of the dance into a national dance craze speaks to the legacy of Black Bohemia. The works of many of these composers and writers laid the groundwork for the emergence of iconic Black musical theater, and ultimately the emergence of the Charleston as a nationwide dance owes as much to musical theater as it does to the jazz scene.6 In 1921, Black musical theater enjoyed a major popular culture breakthrough with the premiere of Shuffle Along. Penned by the seminal composers Eubie Blake and Noble Sissle, Shuffle Along premiered just east of San Juan Hill at the 63rd Street Music Hall. It became a bona fide hit, enjoying both critical and financial success, and ultimately paved the way for future musical theater works by Black composers and Black casts. One of them was James P. Johnson’s 1923 work Runnin’ Wild, featuring his now-iconic Charleston. When it reached New York, it too was performed next door to San Juan Hill (this time at the Colonial Theater on Broadway and 62nd) and would enjoy crossover success much as Shuffle Along had. Black Bohemia, San Juan Hill, and the genius of James P. Johnson conspired to get America dancing the Charleston.

El “charlestón” es una obra profundamente tradicional y extraordinariamente moderna a la vez. El hecho de que se convirtiera prácticamente en un sinónimo de baile popular en la década de 1920 pone de manifiesto la profunda deuda de la cultura popular estadounidense con las tradiciones afroamericanas.

Mientras que la música del charlestón pone de relieve para nosotros las variadas prácticas culturales de los múltiples recién llegados a San Juan Hill, la propagación de la danza hasta convertirse en una moda de baile nacional habla del legado de la Bohemia Negra. Las obras de muchos de estos compositores y escritores sentaron las bases para el surgimiento del emblemático teatro musical negro y, en última instancia, la aparición del charlestón como baile nacional debe tanto al teatro musical como a la escena del jazz.6 En 1921, el teatro musical negro disfrutó de un importante avance en la cultura popular con el estreno de Shuffle Along. Creado por los compositores Eubie Blake y Noble Sissle, Shuffle Along se estrenó al este de San Juan Hill en 63rd Street Music Hall. Se convirtió en un auténtico éxito, tanto económico como de la crítica, y acabó allanando el camino para futuras obras de teatro musical de compositores y elencos negros. Una de ellas fue la obra de James P. Johnson de 1923, Runnin’ Wild, con su ya icónico charlestón. Cuando llegó a Nueva York, también se representó al lado de San Juan Hill (esta vez en el Colonial Theater de Broadway y 62nd) y gozaría de un éxito generalizado, al igual que Shuffle Along. La Bohemia Negra, San Juan Hill y el genio de James P. Johnson se conjuraron para que el charlestón se bailara en todo el país.

San Juan Hill had more jazz stories to tell, as a new generation of artists came of age in the afterglow of the innovations of figures like James P. Johnson. Amidst the tension, difficult living conditions, and crime,7 young jazz musicians also found community and family within the neighborhood. Friends and family often supported their efforts, while older musicians in the area gave these future icons their first music lessons. The legendary Benny Carter recalled several thrilling moments in his teenage years holding the cornet bag of Bubber Miley as the slightly elder artist made his way to his gigs with Duke Ellington. Carter, who took lessons from teachers in the area, also enjoyed recounting how he and friends and classmates like Russell Procope (like Miley, another Ellingtonian) would rehearse and play together in their very first bands. Their efforts were generally supported by friends and neighbors; one jazz-loving family friend even opened up her apartment to the young teenagers as a rehearsal space!8

For these young artists coming of age in the 1920s, San Juan Hill helped provide crucial foundation and camaraderie, the first stop on their extraordinary musical journeys as both they and jazz itself rose to stardom when the 1920s gave way to the 1930s.

San Juan Hill tiene más historias de jazz para ofrecer, ya que una nueva generación de artistas alcanzó la mayoría de edad en el resplandor de las innovaciones de figuras como James P. Johnson. En medio de la tensión, las difíciles condiciones de vida y la delincuencia7, los jóvenes músicos de jazz también encontraron comunidad y familia en este barrio. Los amigos y la familia solían apoyar sus esfuerzos, mientras que los músicos más veteranos de la zona daban a estos futuros iconos sus primeras lecciones de música. El legendario Benny Carter recordaba varios momentos emocionantes de su adolescencia sosteniendo la bolsa de la corneta de Bubber Miley mientras el artista, algo mayor, se dirigía a sus conciertos con Duke Ellington. Carter, que recibió clases de profesores de la zona, también disfrutaba contando cómo él y sus amigos y compañeros de clase, como Russell Procope (al igual que Miley, otro intérprete de Ellingtonian), ensayaban y tocaban juntos en sus primeras bandas. En general, sus esfuerzos contaban con el apoyo de amigos y vecinos; una amiga de la familia, amante del jazz, llegó a abrir su apartamento a los jóvenes adolescentes como lugar de ensayo.8

A estos jóvenes artistas que alcanzaron la mayoría de edad en la década de 1920, San Juan Hill les proporcionó una formación y una camaradería cruciales, la fase inicial de sus extraordinarios recorridos musicales, ya que tanto ellos como el propio jazz alcanzaron el estrellato cuando los años 20 dieron paso a los años 30.

It’s impossible to imagine jazz’s development during this time without the artists who grew up in San Juan Hill. From Rex Stewart’s shining cornet work with bandleaders like Fletcher Henderson to Edgar Sampson’s brilliant arranging for Chick Webb and Benny Goodman, the works of these onetime neighbors were a source of comfort and joy to millions of Americans.

Es imposible imaginar el desarrollo del jazz durante esta época sin los artistas que crecieron en San Juan Hill. Desde el brillante trabajo de Rex Stewart con directores musicales como Fletcher Henderson hasta los brillantes arreglos de Edgar Sampson para Chick Webb y Benny Goodman, las obras de estos otrora vecinos fueron una fuente de consuelo y alegría para millones de estadounidenses.

La influencia de San Juan Hill siguió manifestándose en el jazz cuando otra generación llegó a la mayoría de edad en el barrio. Si bien varios iconos de la revolución del bebop procedían de San Juan Hill, ninguno fue tan genial como el incomparable Thelonious Monk.

Moving to the neighborhood as a young boy in 1922, Monk’s story reflects the story of many San Juan Hill residents: born in the South, Monk found himself in San Juan Hill at the urging of a cousin who had laid down roots in the neighborhood and who served as an initial home for the family following their arrival in the new city.

La historia de Monk, que se trasladó al barrio en su adolescencia en 1922, refleja la de muchos residentes de San Juan Hill: nacido en el Sur, Monk se instaló en San Juan Hill a instancias de un primo que se había establecido en el barrio y que ofreció su hogar inicialmente a la familia tras su llegada a la nueva ciudad.

As had occurred with his predecessors Johnson, Carter, Procope, and others, Monk found himself in an extraordinary assemblage of cultures, much of which can be heard in his own playing and writing. The sounds of church services, the works of fellow jazz artists, even the record players of neighbors spinning the latest hits from the Caribbean all echo in Monk’s works. In fact, some of Monk’s music, particularly “Bye-Ya” and “Bemsha Swing,” serves as a potent reminder of the profound influence Caribbean immigrants had on American popular music. “Bemsha Swing” in particular reflects this: co-written with Monk’s friend and onetime neighbor Denzil Best, the work is a direct homage to Best’s own birthplace of Barbados.9

What might have continued had San Juan Hill not been demolished to make way for Lincoln Center and other developments? We can only hazard guesses and conjectures, as the 1950s brought with it the displacement of this community, leaving us with only hindsight of its story and impact. Ultimately, it was a neighborhood that served as home to thousands upon thousands of new arrivals to New York, seeking new opportunity and stability, hoping for brighter futures, and struggling to achieve a new comfort and freedom.

Al igual que ocurrió con sus predecesores Johnson, Carter, Procope y otros, Monk se encontró con un extraordinario conjunto de culturas, muchas de las cuales pueden identificarse en su propia interpretación y escritura. Los sonidos de los servicios religiosos, las obras de otros artistas de jazz e incluso los tocadiscos de los vecinos que hacían sonar los últimos éxitos del Caribe resuenan en las obras de Monk. De hecho, parte de la música de Monk, en particular “Bye-Ya” y “Bemsha Swing”, es un potente recordatorio de la profunda influencia que los inmigrantes caribeños tuvieron en la música popular estadounidense. “Bemsha Swing”, en particular, es un reflejo de ello: escrita conjuntamente con el amigo y antiguo vecino de Monk, Denzil Best, la obra es un homenaje directo al lugar de nacimiento del propio Best, Barbados.9

¿Qué habría sucedido si San Juan Hill no hubiese sido demolido para dar paso al Lincoln Center y a otros desarrollos? Solo podemos aventurar conjeturas y suposiciones, ya que la década de 1950 trajo consigo el desplazamiento de esta comunidad, dejándonos solo una visión retrospectiva de su historia e impacto. En última instancia, fue un barrio que sirvió de hogar a miles y miles de recién llegados a Nueva York, en busca de nuevas oportunidades y estabilidad, con la esperanza de un futuro más próspero, y luchando por alcanzar un nuevo espacio de comodidad y libertad.

In the story of Black music in New York City, San Juan Hill provides the musical and geographic link between the innovations of the 19th century and the flowering of the Harlem Renaissance.

En la historia de la música negra en la ciudad de Nueva York, San Juan Hill proporciona el vínculo musical y geográfico entre las innovaciones del siglo XIX y el florecimiento del Renacimiento de Harlem.

Demonizado en la prensa popular de la época, romantizado hoy en día en los recuerdos, sigue siendo innegablemente vital en la historia de la ciudad de Nueva York, en la historia de la música negra y en la historia de miles y miles de familias y sus descendientes.

1 Sacks, M. (2006) Before Harlem: The Black Experience in New York City Before World War 1. University of Pennsylvania Press

2 Benjamin R. (1976). [Liner notes]. In Black Manhattan [CD]. New York: New World Records.

3 Johnson, J.W. (1991) Black Manhattan. DaCapo Press. (Original work published 1930)

4 Smith. W., (1964) Music on My Mind: The Memoirs of an American Pianist. Doubleday.

5 Brown. S., Hilbert. R (1986) James P. Johnson: A Case of Mistaken Identity. The Scarecrow Press and the Institute of Jazz Studies, Rutgers University.

6 Lowe, A. (2006) That Devilin'Tune: A Jazz History, 1900-1950. Music and Arts Program of America.

7 Kelley, R.D.G. (2010) Thelonious Monk: The Life and Times of an American Original. Free Press.

8 Berger, E., Berger, M., and Patrick, J. (2002) Benny Carter: A Life in American Music, 2nd edition. The Scarecrow Press and the Institute of Jazz Studies, Rutgers University. (Original work published 1982)

9 Kelley

1 Sacks, M. (2006) Before Harlem: The Black Experience in New York City Before World War 1. University of Pennsylvania Press

2 Benjamin R. (1976). [Liner notes]. In Black Manhattan [CD]. New York: New World Records.

3 Johnson, J.W. (1991) Black Manhattan. DaCapo Press. (Original work published 1930)

4 Smith. W., (1964) Music on My Mind: The Memoirs of an American Pianist. Doubleday.

5 Brown. S., Hilbert. R (1986) James P. Johnson: A Case of Mistaken Identity. The Scarecrow Press and the Institute of Jazz Studies, Rutgers University.

6 Lowe, A. (2006) That Devilin'Tune: A Jazz History, 1900-1950. Music and Arts Program of America.

7 Kelley, R.D.G. (2010) Thelonious Monk: The Life and Times of an American Original. Free Press.

8 Berger, E., Berger, M., and Patrick, J. (2002) Benny Carter: A Life in American Music, 2nd edition. The Scarecrow Press and the Institute of Jazz Studies, Rutgers University. (Original work published 1982)

9 Kelley

If you have questions about the media featured on this site, please email [email protected].

Top image courtesy of: William P. Gottlieb/Ira and Leonore S. Gershwin Fund Collection, Music Division, Library of Congress.

Si tiene preguntas sobre los medios que aparecen en este sitio, envíe un correo electrónico a [email protected].

Traducido al español por GoDiversity.com.

Imagen superior por cortesía de: Colección del Fondo William P. Gottlieb/Ira y Leonore S. Gershwin, División de Música, Biblioteca del Congreso.